I take strange vacations. When I go to Malibu, I spare no time for the beach. Instead, I pack a notebook and a pencil (not a pen!), carefully wash the oils from my hands, and go hunting for ghosts. When I go to Malibu, I plant myself in the reading room at Payson Library for hours at a time and pore over archival records.

For the most part, leafing through a stranger’s long-undisturbed files is as dull as you would expect—so much stirring in dust. But sometimes in the archives I can’t escape the feeling that I have come into contact with something. Sometimes I get the sense that something has been waiting a long time for me to come and stir in its dust.

And this is one of those times.

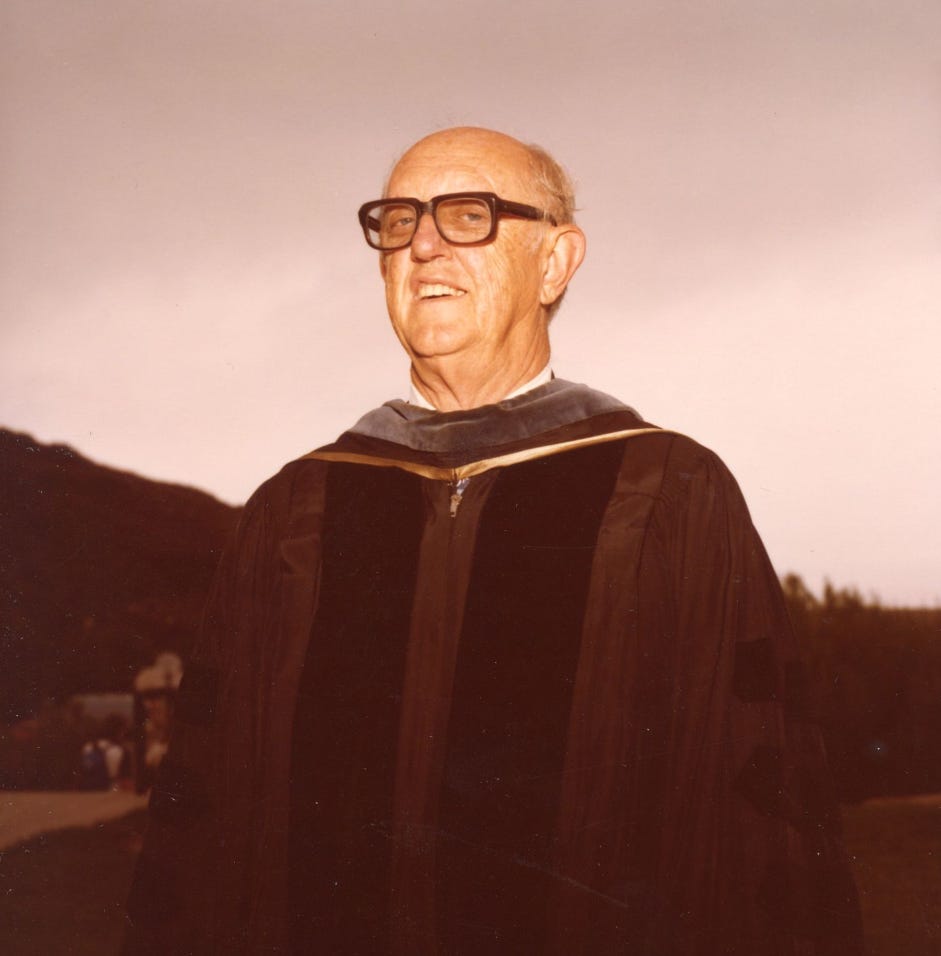

Howard Ashley White was the fifth president of Pepperdine, guiding the university from 1978 to 1985. He left 79 boxes of his papers to the university archives: correspondence, meeting minutes, financial records, newspaper clippings, and so on. But the most interesting parts of the White papers are in boxes 63 and 64, which have prompted the most extraordinary experience I’ve had in the archives.

Boxes 63 and 64 are stuffed with daily memos typed by White himself, who couldn’t entrust his secrets to dictation.1 I like to imagine him during those years coming home from a long day at work, putting his children to bed (he was a single father following the death of his wife Maxcine in 1973), and then sitting down at his typewriter to record the day’s impressions.2 White was trained as a historian, so he had a sense of how powerful archives can be. In his retirement, he took special care to organize these typewritten memos, full of his real-time thoughts about what was happening at Pepperdine.

At some point, White had planned to use these materials to write a history of the 1970s at Pepperdine,3 but illness prevented him from completing the project, so he donated the papers to the university, asking that they remain under seal for some decades to avoid giving offence to anyone still living. Included among the papers is a brief introduction to the restricted materials in which White explains, “I hope that in time to come, some honest, sincere, Christian person will examine these papers and will write the results of his studies.”4

No longer restricted, the materials in these boxes are so rich that histories of the period written without reference to them now seem sadly incomplete. They were available to David Baird when he was writing Quest for Distinction, and I have made repeated reference to them in my writing here, including most recently in my history of Gerald Ford’s visit to Malibu in 1975.5 They can’t have been read by many others.

White’s memos give us a glimpse into personal dynamics among Pepperdine’s top administrators during one of the most consequential periods of its history. But they also let us get to know White—his thoughts on major developments at Pepperdine, his opinions of his colleagues, his hopes, and his fears.

The more time I spend with White’s memos, the more I find to like about him. But the thing I find most admirable is his piety. By piety I don’t mean a narrow dogmatism or an unthinking devotion, but a respect for duty, a careful attention to our obligations to each other, and a reverence for what ought to be revered. White was, of course, a faithful man of God, serving twelve years as a preacher in New Orleans before becoming a professor. But his piety extended beyond his work in the church.

I can’t think of the word piety without seeing in my mind’s eye a tableau from the Aeneid. Vergil’s hero, pius Aeneas (“pious Aeneas”), escapes the flaming towers of Troy, taking his son by the hand and carrying his father on his back, even as his father carries the household gods.6 Aeneas’s pietas (“piety”) is encapsulated here—his ready observance of duties to future generations, to past generations, to country, and to God.

I see White’s piety most clearly in a theme that runs through many of his memos: an intensely-felt duty to preserve for future generations the mission of Pepperdine as it was understood by its founder. From the earliest memos, White is haunted by the prospect of secularization at Pepperdine. He conceived of his project as a record of how a Christian college loses its religious affiliation: “I have read of church-related institutions that changed their character, little dreaming that I would ever be personally involved in such a situation. So in part I think it may be of some interest to write down what occurs in order to provide some evidence of how it all came about.”7

The chief drama of the memos is White’s sustained effort to resist the forces that he thought would lead to the secularization of the university. This struggle manifested itself in different ways as White’s role at the university changed. Sometimes, White could do little more than pray for the health of those he regarded as the great bulwarks of the university’s church affiliation.8 At several points he slipped toward despair: “I see no possible way the institution can avoid becoming secular unless by some providential intervention.”9

But as executive vice president (1971–1978) and then as president (1978–1985), he did have some power to protect the church relationship. The memos often show him shrewdly out-maneuvering those who wanted to sever the university’s religious ties, whether that meant whipping his allies’ votes ahead of a board meeting10 or suggesting someone stay out of the office until an important vote had passed, to dodge an inconvenient phone call.11 White chose his battles wisely, sometimes forthrightly making the case for his preferred policies, and other times consoling himself after a compromise, “It was best to go along in good spirit if I am going to work with him.”12

By the end of his presidency, White was satisfied he had done what he could to secure the church relationship: “It has been my aim during the years I have been associated with Pepperdine to try to make it the best school academically that we could make it, but at the same time to hold on to the Christian ideals upon which it was founded.”13 By this late point, he regarded the threat to the school’s Christian identity as having abated at least in the short term. In retirement, White’s interpretation of the history he had witnessed was a story not of how the school lost its character, but of how “the school almost lost its affiliation with the church” (emphasis mine).14

He maintained to the end the same reverence for Pepperdine’s Christian mission and the same outrage at those who would alter it, writing of one such group: “It was immoral to subvert the school that George Pepperdine had founded. […] By what principle of ethics or reason do they have the right to move in and attempt to take over the property that he paid for and change its mission to suit their own notions?”15

But White was also humble about his perspective and his position in history, confessing, “I do not know if anybody will ever read this. If anybody does, it may be that I shall then be regarded as an eccentric ignoramus, and that there never was any justification for having a school such as Pepperdine now is.”16

By comparing him to Aeneas, I don’t mean to suggest that White was a hero escaping the flaming towers of Watts and founding a new nation in the blessed hills of Malibu to enjoy a millennium of empire. But he did embody some of Aeneas’s virtues, recognizing gratefully the sacrifice of those who came before and striving earnestly to secure their blessings for unborn generations. In the daily work of providing for the education of the youth, he carried with him always Pepperdine and Pepperdine’s God.

If you want to understand today’s Pepperdine, it helps to understand what happened at the university in the 1970s. And to understand the ’70s at Pepperdine, you can do worse than to study the memos of Howard A. White and his legacy of piety.

White, memo to file, 15 Oct. 1981, Box 64, Howard A. White papers (HAWP), Pepperdine University Special Collections and University Archives (SCUA): “Cannot dictate lest word get around the office.”

See, e.g., White, memo to file, 30 June 1976, Box 64, HAWP, SCUA: “This typing is bad for I am trying to use a new eledtric [sic] machine I have given Larryn Bean [recte Larry Bean] for his graduation.” White’s typing in the memos is characteristically littered with mistakes, no matter the typewriter, as if to say with the Apostle, “See, I write this with my own hand.”

See the preface to White, “Crisis at Pepperdine College: A Decisive Change in Administration 1957–1958,” “Introduction” folder, Box 63, HAWP, SCUA: “I would like to live long enough to revise this account into more interesting and readable form, but before starting that, I must work on a much longer project relating to the threatened secularization of the university in the 1970s.”

Introduction to restricted files, Box 63, HAWP, SCUA.

The White papers have been re-arranged since Baird’s work. Baird calls the boxes “xx1” and “xx2” and refers to White’s memos as journal entries or diary entries in various places. I have preferred to cite them as memos to file.

See Vergil, Aeneid 2.707–724.

White, memo to file, 13 Jan. 1974, Box 63, HAWP, SCUA.

“I have been thankful that he [viz., Norvel Young] wants to keep the school close to the church and pray continuously that his life may be spared to help retain this identity.” White, memo to file, 12 Jan. 1975, Box 63, HAWP, SCUA. See also White, memos to file, 25 July 1974 and 18 Sept. 1975, Box 63, HAWP, SCUA.

White, memo to file, 3 July 1976, Box 64, HAWP, SCUA. Cf. White, memo to file, 12 Jan. 1975, supra note 8: “I do not doubt that Pepperdine will become secularized in a few years, at best.”

He reports a plan to “try to program some of the Regents against any proposal to make a change” in White, memo to file, 25 Sept. 1979, Box 64, HAWP, SCUA.

White, memo to file, 15 Oct. 1981, supra note 1.

White, memo to file, 3 July 1976, supra note 9.

White to David Baird, 20 Feb. 1990, “Introduction” folder, Box 63, HAWP, SCUA.

Ibid. Cf. Introduction, supra note 4: “the school almost lost its Christian identity in the decade of the 1970s.”

White, “Crisis,” supra note 3: 47–48. Cf. White, memo to file, 27 Jan. 1977, Box 63, HAWP, SCUA: “I consider it most immoral to break the ties with the church and go contrary to the wishes of our founder, no matter how much money has been piled on top of the original donation of Mr. Pepperdine.”

White, “Crisis,” supra note 3: 48.

I wish I had met him.

An older friend of mine had spent some time with him — and simply adored him.