It’s hard to pinpoint when exactly Pepperdine went from being a college of merely local significance to a university of national or even international renown. Maybe it happened with the launch of Pepperdine’s first international program in Heidelberg in 1963, or when it first claimed university status in 1971, or when the Malibu campus opened in 1972, or when former California governor Ronald Reagan dedicated Seaver College in April 1975. But for my money, the transformation occurred on September 20, 1975. That Saturday morning, a helicopter landed on Pepperdine’s soccer field, and out climbed the president of the United States.1

Gerald Ford is a strange figure in American history, being the only president who was never elected to either the presidency or the vice presidency. (He was appointed Richard Nixon’s VP after the 1973 resignation of Spiro Agnew and assumed the presidency when Nixon resigned in 1974.) His appearance in Pepperdine’s story cries out for explanation: how did Pepperdine of all places secure a visit from the president?

Why did Ford come?

The ostensible reason for Ford’s visit was the dedication of the Brock House and the Firestone Fieldhouse. Both buildings had stood for years by the time of their dedication, but the ceremony was delayed, partly because Leonard K. Firestone, the namesake of the fieldhouse—and yes, this is Firestone like the tires—was serving abroad as Nixon’s (and later Ford’s) ambassador to Belgium. But why should Ford of all people be the one to dedicate the gymnasium and the president’s home?

The beginning of an answer has to do with the donors behind these two buildings. Margaret Martin Brock, the namesake of the Brock House on the Malibu campus, was a major political donor in the California GOP and an important supporter of Ford’s 1976 re-election campaign, which was already underway when he agreed to visit Malibu.2 Firestone and Ford were friends—following Ford’s electoral loss in 1976, the president and his wife would move in next door to the Firestones in Rancho Mirage, California.3

Because Brock and Firestone both had ties to the president, it made sense that the buildings they funded were used as the bait to draw him in. They were also both supporters of Pepperdine, which was not a coincidence. For over a decade at that point, the university’s fundraisers had been making common cause with the Republican party, and many of Pepperdine’s most generous donors were active in politics.

So you might tell the story like this: How did Pepperdine get the president to come to Malibu in 1975? By building a fundraising operation on a foundation of conservative politics that appealed to an incumbent Ford who was eager to capitalize on their overlapping audience to gain support for his re-election campaign.

This is more or less the story as it’s told in the memoir of William S. Banowsky, who was Pepperdine’s president at the time and one of the architects of the university’s fundraising strategy. In his version of the story, “President Ford, friend of Margaret Brock and Leonard K. Firestone, was coming to Pepperdine to honor both.”4 I don’t doubt there is substantial truth to this account, but I think there’s more to the story.

First, Banowsky’s memoir makes some important errors in relating the timeline of Ford’s visit to Malibu. He repeatedly says it wasn’t until after Ford’s visit that he (Banowsky) was considered for a position in Ford’s Department of the Interior, dating the event to January 1976.5 In fact, it was July 1975—before Ford’s visit—that Banowsky traveled to Washington D.C. to meet with congressional leaders about the possibility of being appointed undersecretary (and later secretary, to replace the hospitalized secretary Stanley Hathaway, who had offered Ford his resignation).6

Why was Ford so eager to get Banowsky into a cabinet-level position? First, Banowsky was an important figure in the California GOP, serving formally as the Republican National Committeeman and informally as an influential figure among wealthy donors. Second, Banowsky had recently endorsed Ford for re-election.7 Banowsky later wrote that he felt tricked into endorsing Ford before he knew that Ronald Reagan planned to challenge the incumbent for the GOP nomination in 1976.8 Getting the endorsement of conservative Republicans like Banowsky was important if Ford wanted to fend off the primary challenge, so the offer of the position at Interior may have been in recognition of Banowsky’s loyalty at the expense of his friend Reagan.

Whatever Ford’s reasons for making the offer, Banowsky quickly decided against taking the position, but the reasons he gave in the national press seem like excuses.9 According to a diary entry by Banowsky’s executive vice president Howard White, the “real reason he got out of the picture” was an ongoing IRS investigation into Banowsky’s finances that promised to make Senate hearings unpleasant.10

It’s in the wake of this undersecretary debacle that Banowsky announced president Ford would come to Malibu to dedicate the fieldhouse. In fact, many sources dealing with Banowsky’s sudden rejection of the role at Interior also make note of Ford’s promised visit.11 It seems reasonable, therefore, to speculate that Ford may have agreed to the visit in order to repay Banowsky for any embarrassment stemming from the aborted appointment. Pepperdine historian David Baird connects the dots between the rejected Interior position and the invitation to Malibu:12

“Ford’s acceptance seems more like a response of thanks to Banowsky for his public support and as salve for the insult the Pepperdine president had suffered at the hands of the press and members of the U.S. Congress when his name had been mentioned for the Interior Department position. Ford owed Banowsky a favor, actually many favors, and he agreed to speak on the Malibu campus.”

Preparing for the visit

Pepperdine took on significant expenses to prepare for Ford’s visit, when the nation’s attention would be focused on the new campus. At least $30,000 of landscaping was done, which the university tried to save money on by refusing to hire outside contractors. President Banowsky himself was seen, shovel in hand, contributing to the effort.13 Temporary seating had to be installed in the fieldhouse parking lot, and parking had to be arranged for an expected crowd of 15,000 (the actual number ended up being estimated at 18,000).14

Perhaps the biggest expense was the construction of a staircase climbing from the fieldhouse lot up to the Scaife Bridge and Terrace behind the Tyler Campus Center. Several retaining walls were necessary, bringing the cost of the work to some $70,000.15 The university also installed a giant concrete sign on the side of the bridge, reading “Seaver College.”16 According to legend, the reason for this last-minute addition (visible from the fieldhouse lot) was to comfort Blanche Seaver, the major donor who would be in attendance and might be distressed by so much talk of Pepperdine and so little of the Seaver name—a sore point with her.

One of the most lasting of the preparations for the Ford visit was the introduction of the university’s flag, designed for the event and still in use today. The banner, featuring three horizontal bands of blue and white waves beneath an orange sky, was the product of a collaboration between first lady Gay Banowsky and architect Peter Munselle, who had also designed the Brock House and the Firestone Fieldhouse.17

These preparations came at an especially difficult time for Pepperdine, which was under tremendous financial strain due to debt remaining from the construction of the Malibu campus. The university had trouble making payroll that September, borrowing even more money to do so, with major payments due on construction loans and the finance office unable to collect millions of dollars in accounts receivable because of computer problems.18 Everyone involved seems to have believed that the costs of preparation were a worthy investment given the publicity to be brought by the president’s visit.19

To make matters worse, the campus was hit by back-to-back tragedies in the week before Ford arrived. On the Monday before the Saturday visit, an on-campus motorcycle accident killed 36-year-old math professor Charles Wilks.20 Then on Tuesday, university chancellor Norvel Young was arrested in a drunk-driving accident that killed two women on PCH near the Getty Villa.21 News of the accident reached Ford’s chief of staff Donald Rumsfeld, who nearly cancelled the president’s visit. Ford himself was already on edge after surviving an assassination attempt in Sacramento two weeks prior.22

The Ford visit

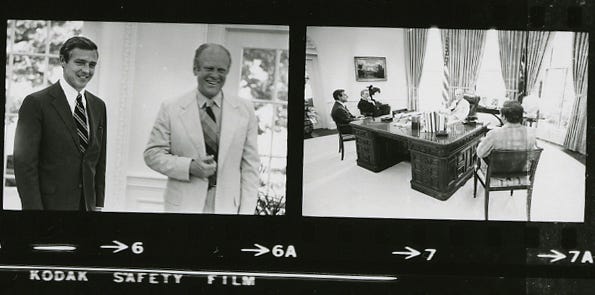

In spite of all these challenges—the financial struggles, campus tragedies, and security needs—the president’s visit went as planned. Ford arrived on Marine One at the soccer field at 10:10am, where he was greeted by the Banowskys and whisked off to the Brock House by the presidential motorcade to shake hands with a few hundred VIPs over brunch.23 Ford signed some autographs and made brief remarks to honor Brock’s support of Pepperdine.

While Ford was schmoozing up the hill, crowds had already gathered in the stands to see the president dedicate the fieldhouse. A Marine band from the El Toro base entertained the audience with patriotic tunes while they waited, sweltering in the sun. Celebrities and Pepperdine students took turns on stage, too: Danny Thomas told some jokes, and alumnus Shannon Goodwin sang a song.24

Ford met briefly with a small group of Pepperdine students while getting into his academic regalia for the dedication of the fieldhouse. The ceremony itself was held in the parking lot in front of the fieldhouse to accommodate a crowd that has been called the largest ever assembled in Malibu. The star-studded program included the national anthem performed by Pat Boone and the pledge of allegiance led by actor John Wayne. There were musical performances by the Marine band and by Pepperdine’s a cappella chorus. Trustee Reuel Lemmons said a prayer. Leonard Firestone formally offered the fieldhouse to the university, and Richard Seaver accepted it on behalf of the university.25

Then president Ford received an honorary doctorate from Pepperdine donor Richard Scaife. The president delivered an address on the importance of private colleges and universities like Pepperdine, praising Banowsky’s role in building the Malibu campus, and formally dedicating the fieldhouse. He stated his support of tax deductions for charitable donations made to private education.26 Banowsky had negotiated through back channels to write the president’s address.27

Following the ceremony, Ford was whisked by motorcade back to the makeshift helipad and flew off to LAX to carry on with his busy schedule. The next day, he spoke at a dedication ceremony at Stanford Law School; the day after that, he would survive another assassination attempt, his second that month.

Epilogue

Ford’s electoral loss to Jimmy Carter in 1976 ended his presidency, but his association with Pepperdine was only getting started. Just a week after the election results were reported, Banowsky offered to make Ford chancellor of Pepperdine, to replace Norvel Young, who was on leave following his accident. Ford considered but ultimately rejected the chancellory.28 Years later, however, he agreed to serve alongside Leonard Firestone and Margaret Brock on the university’s Board of Regents, a position he evidently held for six years before becoming a (non-voting) Life Regent.29

Ford’s visit was in some ways the capstone of Banowsky’s efforts at Pepperdine. Between 1968 when Banowsky came back from Lubbock and that day in 1975, the institution was transformed from a small liberal arts school in a run-down neighborhood to a university with a sparkling new campus in Malibu, a suite of graduate and professional schools, an international presence, and the support of the rich and powerful. It became, in short, the sort of place the president of the United States might treat more or less as he treated Stanford. Banowsky, of course, was not alone in bringing about this transformation, but he deserves much of the credit, especially for securing the visit from president Ford.

Photographs of the makeshift helipad show it on the soccer field at the track. Strangely, Banowsky makes a special note of remembering the helicopter as landing on the baseball field (Malibu Miracle, infra note 4: 325), and Baird follows him in this error (Quest, infra note 12: 301). Reporters for the student newspaper unambiguously state that the soccer field was used. See “Pepperdine hosts presidential visit,” The Graphic, 26 Sept. 1975: 4.

Brock appears in passenger manifests for Air Force One in 1975. See, e.g., “The Daily Diary of President Gerald R. Ford,” 30 Oct. 1975, box 78, President’s Daily Diary Collection, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library (GRFPL): 6.

The Firestones lived in a home designed by William Pereira at 40555 Sand Dune Road, and the Fords moved in next door at 40471, overlooking the thirteenth fairway at the Thunderbird Country Club outside Palm Springs.

William S. Banowsky, The Malibu Miracle: A Memoir, Pepp. Univ. Press, 2010: 323.

Banowsky supra note 4: 106, 327. Despite hours of research in various databases of the LA and NY Times, I have not been able to confirm any of the newspaper articles Banowsky cites in favor of his timeline at the end of chapter 6.

See Ben A. Franklin, “Hathaway Offered His Resignation on Entering Hospital, but Ford Rejected It,” New York Times, 24 July 1975: 15. Cf. Neva Hash, “Banowsky dispels political rumors,” The Graphic, 15 July 1975: 1. See also Douglas P. Bennett to Philip Buchen, 17 July 1975, box 40, folder “Personnel - Security Waivers (1),” Philip Buchen Files, GRFPL: 40.

The timing of Banowsky’s endorsement is difficult to pin down precisely. As Banowsky tells it, he agreed to endorse Ford the evening of May 10, 1975, and the newspapers printed the endorsement the next day (Malibu Miracle: 105–106). I can’t find any mention of the endorsement in the papers until July 10. See Richard Bergholz, “Longtime Reagan Backers Join Ford,” Los Angeles Times, 10 July 1975: 1.

See Banowsky, Malibu Miracle: 105–106. Banowsky wasn’t alone; he was joined by friends and Pepperdine supporters including Henry Salvatori and Margaret Martin Brock. See Bergholz supra note 7.

Banowsky told the Los Angeles Times that he decided against taking the position (1) because his family did not want to move, (2) because the appointment would not go through until September, and (3) because he could only secure a one-year leave from the Pepperdine trustees. The Times also reported that Banowsky may have encountered some resistance from members of the Senate Interior Committee, including Paul Fannin (R-Ariz.) and chair Henry M. Jackson (D-Wash.). See Gaylord Shaw, “Banowsky: Why Nomination for U.S. Post Didn’t Come Off,” Los Angeles Times, 29 July 1975: 3, 16. Perhaps also relevant was the fact that reporters were sniffing around Banowsky’s involvement in the Trent Devenney affair. Some speculated that Banowsky was in a hurry to get back to Malibu because “he was having faculty problems.” See Franklin supra, note 6. While Banowsky certainly did have faculty problems in 1975, I’m not sure about the timing of this allegation.

For his part, White was persuaded that Banowsky was innocent of wrongdoing, which he trusted the IRS investigation would soon find. See Howard White to file, 26 July 1975, box 63, “Church Relation: July 1975” folder, Howard A. White papers (HAWP), Pepp. Univ. Special Collections and Univ. Archives (SCUA).

See Franklin and Hash supra note 6, Shaw supra note 9, and White supra note 10.

W. David Baird, Quest for Distinction: Pepperdine University in the 20th Century, Pepp. Univ. Press, 2016: 300. Note, though, that Baird was unsure when Ford agreed to come to Malibu. His speculation is seemingly strengthened by the simultaneity of Banowsky’s withdrawal from consideration and Ford’s acceptance of the invitation to Malibu.

Michael A. Palladino, “President’s arrival speeds improvements,” The Graphic, 26 Sept. 1972: 1. Other sources put the cost of landscaping at $70,000. See Norvel Young to whom it may concern, box 23, “Young, M. Norvel -- Car Accident” folder, William S. Banowsky papers, SCUA: 5.

Neva Hash, “Ford to dedicate Pep facilities,” The Graphic, 19 Sept. 1975: 1.

Baird, supra note 12: 300.

Palladino, supra note 13.

See “Architect designs new flag,” Inner View, 17 Oct. 1975: 3; cf. Michael A. Palladino, supra note 13.

Young to whom it may concern, supra note 13: 3.

See, e.g., Howard White to file, 8 Sept. 1975, box 63, folder “Church Relation Sept. 1975,” HAWP, SCUA. Cf. Young to whom it may concern, supra note 13: 5.

“Fatal accident,” The Graphic, 19 Sept. 1975: 1; cf. “Memorium”: 3.

“Young faces charges,” The Graphic, 19 Sept. 1975: 1.

Baird, supra note 12: 300–301. Cf. Banowsky, supra note 4: 332.

“The Daily Diary of President Gerald R. Ford,” 20 Sept. 1975: 2.

Audio recordings of the event are available here: “President Gerald Ford Speaks at the Dedication of the Firestone Fieldhouse.”

Lee Ann Park, “Ford encourages support of independent education,” The Graphic, 26 Sept. 1972: 1.

Gerald R. Ford, “Remarks at Dedication Ceremonies at Pepperdine University, Malibu, California,” 20 Sept. 1975, The American Presidency Project.

Baird, supra note 12: 300. Files from Sept. 1975 show the Ford White House working with Banowsky on the text of his address. See, e.g., “Presidential Log,” 15 Sept. 1976, box 2, President’s Paperwork Logs, GRFPL: 7. Cf. Paul A. Theis to President Ford, 9 Sept. 1975, box C27, folder “Presidential Handwriting 9/11/1975,” Presidential Handwriting File, GRFPL: 3.

See Howard White to file, 11 Dec. 1976, Box 64, HAWP, SCUA. Ford’s daily diaries record frequent conversations with Banowsky in December 1976.

I’m unsure of the exact dates of Ford’s service on the board, but it seems to have lasted six years, perhaps 1985–1991. See letters from Margaret Martin Brock dated 6 June 1991 and 10 July 1992. Ford seems to have been an involved member of the board, attending meetings and actively participating. See Brock’s letter to Ford dated 18 June 1987.