Banner yet wave

The history of Pepperdine's flag and its long-lost predecessor

Pepperdine University’s flag is a triumph of design. The school’s official banner sports three ranks of crashing waves alternating blue and white under an orange sunset sky.1 It succinctly ties together the university’s official colors, its team name, and—abstractly, at least—the beauty of its oceanside campus in Malibu at the western edge of the continent, the land of the sunset. The design is so simple that it can be described in the limited language of medieval heraldry, but it is also an abstract representation of the most iconic scene in Malibu, where the sun sets behind swell lines receding to the horizon like so much wide-wale corduroy viewed obliquely.

The symbolic landscape painting of the Pepperdine flag is surprisingly rare in vexillology, with the best analogy being the national flag of Ukraine (per fess, Azure and Or), often interpreted as an abstract depiction of a wheat field under a blue sky.

The Wave flag was hoisted for the first time on September 20, 1975, the day when president Gerald Ford visited the Malibu campus for the dedication of the Firestone Fieldhouse (I’ve written at length about Ford’s visit). Indeed, the university installed at least nine new flag poles around campus in preparation for the big day to show off the new banner alongside the flags of the United States and California.2

The Wave flag was designed by Peter Munselle, the architect behind both the Firestone Fieldhouse and the Brock House, in collaboration with first lady Gay Banowsky.3 Although it was first flown on the day of the president’s visit, it was intended to serve the university beyond that event, and as far as I know, it has been in continuous use since then.

Among the many misconceptions circulating around the time of the Wave flag’s debut was the idea that it was the first official flag Pepperdine had ever had. In fact, there had been an earlier flag that was forgotten by 1975 except among certain aging alumni and longtime members of the faculty.

In 1954, The Graphic announced a contest to design a school flag for George Pepperdine College.4 There were nineteen submissions, but I can only find images of the three finalists.5 One featured the letters GPC in a shield and looked more like a Superman singlet than anything else. Another put the college seal between two ribbons reading “George Pepperdine College.”

The third design was more complicated, with a globe (a polar azimuthal projection borrowed from the flag of the United Nations), a cross, a striding man with a diploma, crashing waves in the background, the founding year of 1937, and a ribbon reading “George Pepperdine College.” This third flag was designed by Bill Squire, a former student who at the time of the contest was serving in the Army and sent in his design from Tokyo. Bill’s father Russel N. Squire was professor of music at the college.

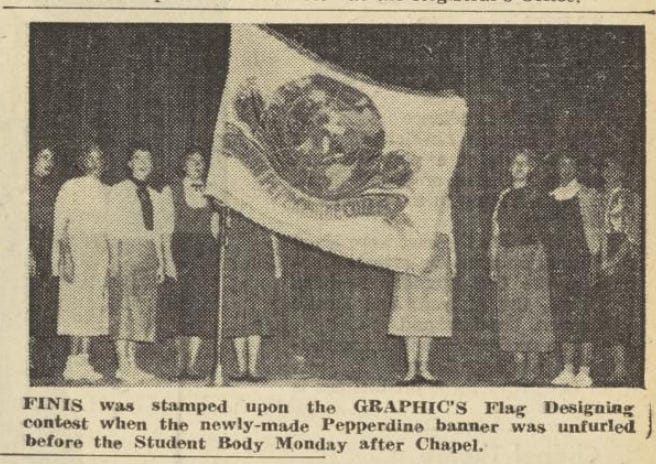

The three finalists had their designs published in The Graphic, and over five hundred ballots were cast by students, faculty, and alumni. Squire’s design was the clear favorite, winning nearly two-thirds of the votes. He received a $50 prize. Thanks to an anonymous sponsor, a real flag was made based on Squire’s design. The flag was unveiled in a special ceremony after chapel on May 10, 1954, and was presented with significant fanfare to president Hugh Tiner. Squire, still on duty in Japan, was represented by his mother. A grainy photo in The Graphic shows students posing with the new flag.6

The story of the flag contest seemed like big news, worthy of significant column-space in The Graphic, and it inspired letters and editorials (“If Betsy Ross Could Do It, Why Not Us?” and “Draw Flag – Win Swag”) as well as front-page skylines normally reserved for big, breaking stories.7 But remember that by 1975, the Squire flag was forgotten to such an extent that most of the reporting on the new Wave flag called it Pepperdine’s first official flag. So what happened in the intervening years?

The biggest change at Pepperdine between the 1954 debut of the Squire flag and the 1975 unfurling of the Wave flag was the move to Malibu. Pepperdine was still operating the Los Angeles campus in 1975 (indeed, the Inner View, the student newspaper in L.A., hailed the arrival of the new flag that year), but the institution’s focus had shifted 24 miles west by north to Malibu.8

I don’t know if the single existing copy of the Squire flag was literally left behind in Los Angeles when Pepperdine sold the campus in 1981. Efforts were made to transfer to Malibu other keepsakes, including the statue Dolores. But by 1988, the Squire flag had been definitively lost, and an effort was made to locate it. University publications asked alumni, “Can you help ‘flag’ down a Pepperdine relic?” and speculated that it might have been stolen by a student group as a prank.9

Nothing ever came of the search that began in the 1980s, but in 2017 the flag suddenly resurfaced. Pepperdine vice chancellor Ronald Phillips was contacted by a law school alumnus named Richard D. English, who had a collection of old university banners. English sent Phillips the old Squire flag with a note saying he thought the university should have it “as part of Pepperdine history.”10 The flag made its way to the university archives, where it remains today. I’ve seen it in person. It is old and it looks old—faded, stained, torn, and patched—but still recognizably Squire’s original design.

I think Pepperdine should do more with the Wave flag: fly it more and include it more fully in the iconography of the institution. I agree with 1954 student body president Chuck Kane, who argued in the pages of The Graphic, “Whether or not a school is new, it needs an abundance of ideals and traditions.”11 And the Wave flag is a fine tradition: evocative and elegantly simple. One of my favorite traditions is when the flag flies at half-staff in memory of lost Waves.12 There’s a quiet dignity about the lowering of the Wave flag in Malibu when a cherished friend has died in Heidelberg. It makes me proud to be a Wave.

The flag has often been described inaccurately as featuring a row of orange waves or four rows of waves. See, e.g., Michael A. Palladino, “President’s arrival speeds improvements,” The Graphic, 26 Sept. 1975: 1; cf. Jim Ruebsamen, “Flag protocol stated,” letter to the editor of The Graphic, 3 Oct. 1975: 6. See also, "Architect designs new flag," Inner View, 17 Oct. 1975: 3.

Palladino, supra note 1.

“Architect designs new flag,” supra note 1.

“Flag Designing Contest Plans, Rules Announced,“ The Graphic, 13 Jan. 1954: 3; cf. “Flag Deadline Coming Soon,” The Graphic, 27 Jan. 1954: 4.

“Flag Contest Finalists Compete for Honors,” The Graphic, 17 Feb. 1954: 1.

“Flag Unveiling Due for After Chapel Monday,” The Graphic, 5 May 1954: 1; cf. “Flag Unveiled in Ceremony,” The Graphic, 12 May 1954: 1.

See, e.g., Virginia Rodman, “Flag Deadline Is Friday,” The Graphic, 10 Feb. 1954: 1.

See “Architect designs new flag,” supra note 1. In one of Inner View’s final issues, the editorial board complained that the Los Angeles campus had been so forgotten that it didn’t even have a Wave flag on campus: “Perhaps if we could see the orange and blue waves [sic] flying over the campus, we could take heart that we hadn’t been forgotten. But the prospect is doubtful.” See “Flag,” Inner View, 2 July 1976: 4.

“Missing flag prompts search,” Pepperdine Voice, Feb. 1988: 5. Mention was also made of the missing Squire flag at an event held in 1987 to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the death of George Pepperdine. See “Luncheon to honor the 25th anniversary of George Pepperdine's death,” 31 July 1987, Pepperdine University Archives Audiovisual Collection: 55:51ff.

Rich English to Dean Phillips, [May 2017], Pepperdine University Special Collections and University Archives.

Chuck Kane, “If Betsy Ross Could Do It, Why Not Us?,” The Graphic, 27 Jan. 1954: 4.

The honor has been afforded many times, including to Hugh Tiner, Helen Pepperdine, Margaret Martin Brock, and Mary Drehsel. I find evidence of the practice as early as 1981, but the official university policy seems to have been first put into place by executive vice president Andrew Benton in 1996. See “University Policy Established for Lowering Pepperdine Flag,” Peptalk, Dec. 1996: 4.

Hi Sam, Thanks for your blog. I am really enjoying them. I especially enjoyed the one chronicling the Harding to Pepperdine professor moves. I will write some of my own recall of what happened during my two years at Harding. The brief visit we had at Pepperdine Lectures this year was wonderful. The Perrin family has a special place in my heart. Sincerely, Richard