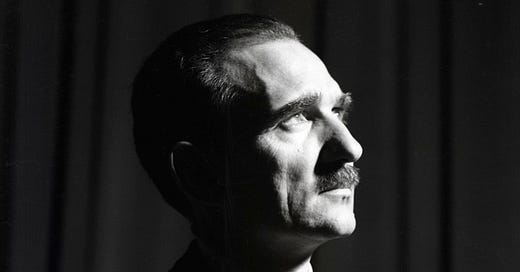

Today is the thirtieth anniversary of the death of Earl Vivon Pullias, who served as dean of George Pepperdine College from 1940 to 1957. Pullias’s contributions to Pepperdine were many, but he was not without critics. He left a complicated legacy.

Pullias was a member of the first faculty at George Pepperdine College. He came to Pepperdine from Duke, where he had received his PhD in educational psychology, making him one of the best-educated members of the faculty. He chaired the psychology department for the college’s first few years before becoming dean in 1940.

As dean, Pullias oversaw the daily operations of the college. David Baird credits him with major curricular innovations,1 and former colleague James Smythe remembers him as embodying the Pepperdine spirit: “Dean Pullias was the quintessential embodiment of ‘the Pepperdine Spirit’ of modesty, service and faith. He lived in a little house. He drove an old car. He gave his money to the poor.”2

But Pullias had some critics among his Church of Christ brethren. His CofC credentials were strong: he served as an elder at the Vermont Avenue congregation next to the college’s campus in South Los Angeles, and his brother, Athens Clay Pullias, served as president of Pepperdine’s sister school David Lipscomb College for over thirty years. But journals of the brotherhood smeared him as theologically “modern,”3 a charge which he was at pains to refute.4

In 1957, Pullias was forced out of both the deanship and the college in a series of events too complex to recount here in their entirety. In short, the Board of Trustees—led by founder and chair George Pepperdine—felt that the board’s plans for the college were at odds with the leadership of dean Pullias. The incoming president that year, M. Norvel Young, wanted to install a dean of his own choosing (J. P. Sanders), and there would be no place for Pullias.

The fight over the deanship in 1957 was hotly contested. The trustees worried that the college’s relationship with the Church of Christ was at risk under the leadership of dean Pullias. But much of the faculty thought Pullias’s vision of a more ecumenical college would allow for superior academics. Ultimately, the trustees had their way. Following the dean’s ouster, a significant minority of the college’s faculty resigned in protest of what they saw as an overly sectarian board. Pullias found a spot on the faculty at USC, where he served the remainder of his illustrious career.5

Since then, Pullias’s name has come to stand for a particular idea among Pepperdine historians: academic excellence, perhaps even at the cost of the institution’s connection to the Church of Christ. Richard Hughes credits Pullias with bringing to Pepperdine “an unyielding commitment to academic excellence,”6 and Howard A. White accuses him of having “no interest in serving the church.”7 Some presidents have self-consciously identified as belonging to one camp or the other, including Bill Banowsky, who declared: “I sought to nourish and expand the larger Christian vision which Earl Pullias had built into the soul of the school, but which had been systematically resisted by his opponents.”8 This divide makes it difficult to assess Pullias’s legacy neutrally—each camp has evaluated his contributions according to their idea of what Pepperdine should be.

The task of evaluating Pullias’s legacy is only further complicated by the fact that Pullias himself seems to have evolved on the question of how Pepperdine should relate to the Church of Christ. In a letter to Bill Banowsky in 1974 (seventeen years after his departure), Pullias wrote, “I have come to believe that it is difficult, perhaps impossible, to have the religious commitment needed to support and maintain an atmosphere with a spiritual component of power without a very close, even intimate, relationship with what most would consider a confining sectarian group.”9

In 1977, Pullias retired as professor of education at USC, which has subsequently honored him with the name of the Pullias Center for Higher Education. In 1986, he attended an event in Malibu honoring the 100th anniversary of the birth of George Pepperdine. Pullias’s gracious remarks at the event suggest that he had reconciled with Young, Sanders, and Pepperdine, and that he was proud of the school’s accomplishments.10 The next year, he wrote to an old Pepperdine friend, “The very cruel dismantling of the original Pepperdine obviously made me resentful. But I’m over that now, and deeply proud of Pepperdine.”11

So what should we make of Pullias’s legacy?

I don’t buy Hughes’s argument that Pullias is responsible for introducing academic excellence to Pepperdine. Whatever his contributions may have been, the rise of the institution’s academic quality largely stems from the success of the Malibu campus, which opened fifteen years after Pullias’s departure. Moreover, under his leadership, the college briefly lost its accreditation in 1951, a fact that Pullias and president Hugh Tiner hid from the Board of Trustees.12

On the other hand, I don’t think it’s fair of White to disregard Pullias’s long service to the college and the church just because of a disagreement about the relationship between the two. While it’s true that the college was at serious risk of dissolution when Young took over in 1957, that wasn’t entirely Pullias’s fault.

The truth is probably somewhere in between. We can both credit Pullias for his contributions and hold him responsible for his shortcomings, especially where he later changed his mind.

Baird et al., “Opportunities for Liberal Learning in the 21st Century,” 1997: 8.

Qtd. in William S. Banowsky, The Malibu Miracle (Pepperdine Univ. Press, 2010): 27.

See O. L. Castleberry, “Is George Pepperdine College Sound,” The Bible Banner 10.3, Mar. 1948: 1–4. Cf. Foy E. Wallace Jr., “Disturbing Reports from the West,” The Bible Banner 10.5, May 1948: 1, 16.

See, e.g., E. V. Pullias, “Some Christian Fundamentals,” The Church and Sound Doctrine, 1947: 17–21.

The best overview of the fight over the deanship is David Baird’s “Searching for Rescuers,” Quest for Distinction (Pepp. Univ. Press, 2016): 85–99.

Richard T. Hughes, “Faith and Learning at Pepperdine University,” Scholarship, Pepperdine University, and the Legacy of the Churches of Christ, 2004: 23.

Howard A. White, “Crisis at Pepperdine College: A Decisive Change in Administration, 1957–1958,” “Introduction to Restricted Files” folder, box 63, Howard A. White papers, Pepperdine Univ. Special Collections and University Archives (SCUA): 46. Note too that White regarded his mission at Pepperdine as being in no small part a response to the college’s failure, under the leadership of dean Pullias, “to meet the approval of a large number of members of the Churches of Christ across the nation.” See Howard White, memo to file, 13 Jan. 1974, “Church Relation Jan. 1974” file, box 63, Howard A. White papers, SCUA.

Qtd. in Hughes, supra note 6: 27.

Qtd. in White, “Crisis,” supra note 7: 53.

See White, “Crisis”, supra note 7: 44–45. Cf. “Luncheon Honors George Pepperdine Centennial 1886-1986,” Pacific Church News, summer 1986: 3.

Qtd. in Banowsky, supra note 2: p. 33, n. 25. Banowsky cites a letter from Pullias to Patsie Trowbridge dated 15 Feb. 1987, from the Pullias papers, SCUA.

See Baird, Quest, supra note 5: 60–63.