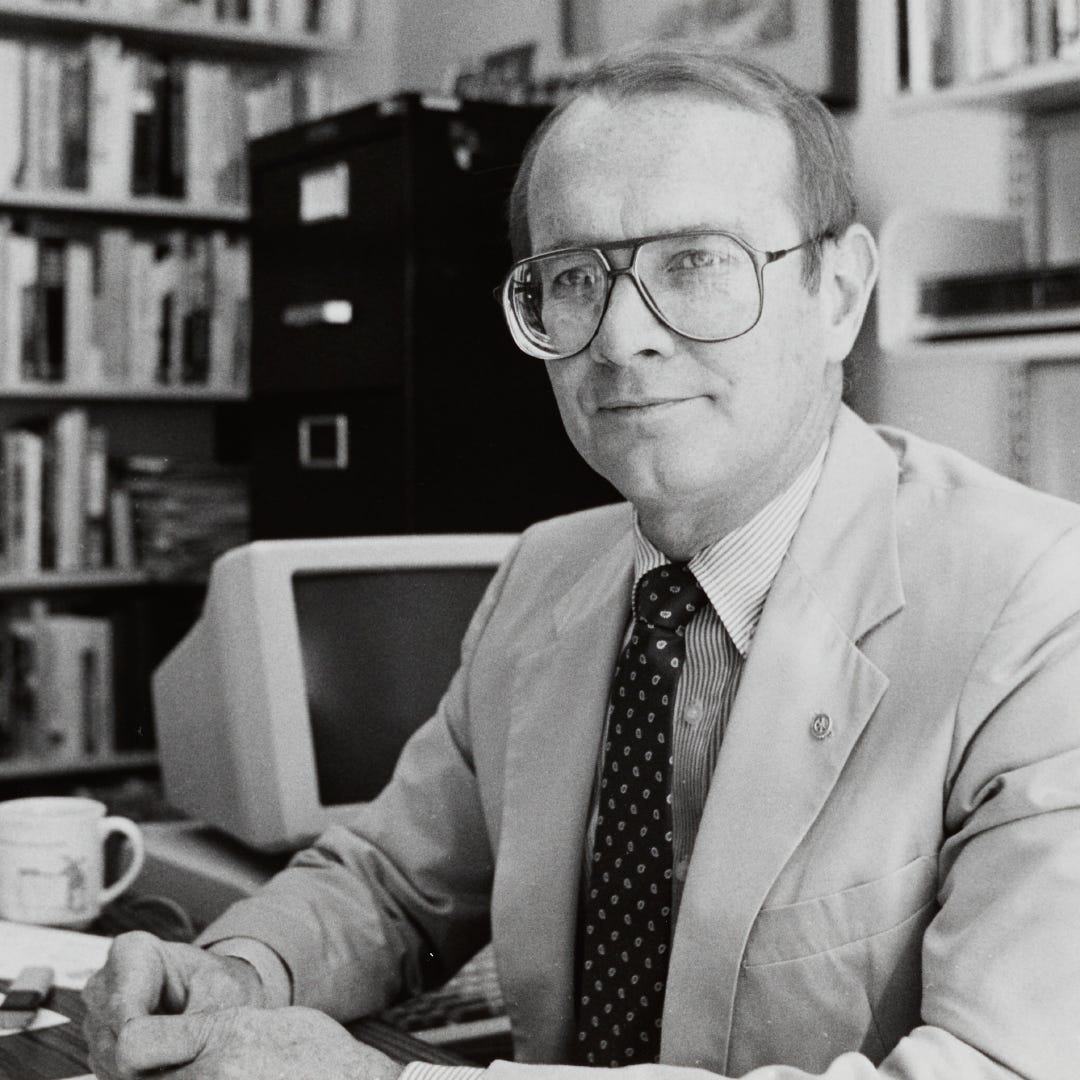

This week I was sad to hear of the death of David Baird, dean emeritus of Seaver College. The news made me think about the man I knew as neighbor and churchman. The tenor of my reflections prompted me to put off history for now, in favor of something more like memoir.

I grew up on a hillside. Across the street from the family home was a ravine that we used to call “the canyon” but which topographical maps of the area call Winter Canyon. Come to think of it, there were at least two canyons in the Santa Monica Mountains where I grew up that we just called “the canyon,” but we never seemed to have any trouble disambiguating them, probably because only one of them (not Winter Canyon—the other one) had a road winding through it.

“Winter Canyon” is the sort of technical moniker that cartographers or geological engineers might need to know when they’re making maps or prognosticating about future earthquakes or whatever but that never seemed all that useful when you lived right up there on the edge of the thing. As a kid, if I was going to play “in the canyon,” there was really only one place I could mean.

I’m not sure where the canyon got its name. I like to think that, in centuries past, the ranchers that owned all those hills would ride horses through them and that maybe this was the canyon where they went riding in the winter, for whatever reason—though of course there isn’t really much of a winter in that part of the world, being more the sort of place that inspires people like the Beach Boys to talk about Endless Summer, which I listened to as a child on compact disc during car rides through the canyon (the other one, naturally).

Winter Canyon is a steep V with walls hundreds of feet high showing lots of exposed bedrock—mostly in a bland khaki color but with some of that pinkish sandstone that makes me think of Wile E. Coyote. At the bottom of the canyon there’s a dry creek bed that I never saw with more than a tiny trickle of water in it, though probably after a big rain it swells to something more substantial.

At the very top of the canyon wall opposite the family home (but a good bit higher) there is a rocky outcropping of the same sandstone, part of which looks like a huge sphere embedded in the earth. For some reason that I could never be made to understand, we called the rock formation “Frog Face,” but I don’t think that name shows up on any maps and I certainly never knew anyone who claimed to be able to make out any sort of amphibious countenance up there. The name was, like the rock itself, just part of the environment I grew up in, rather than something whose origins cried out for explanation.

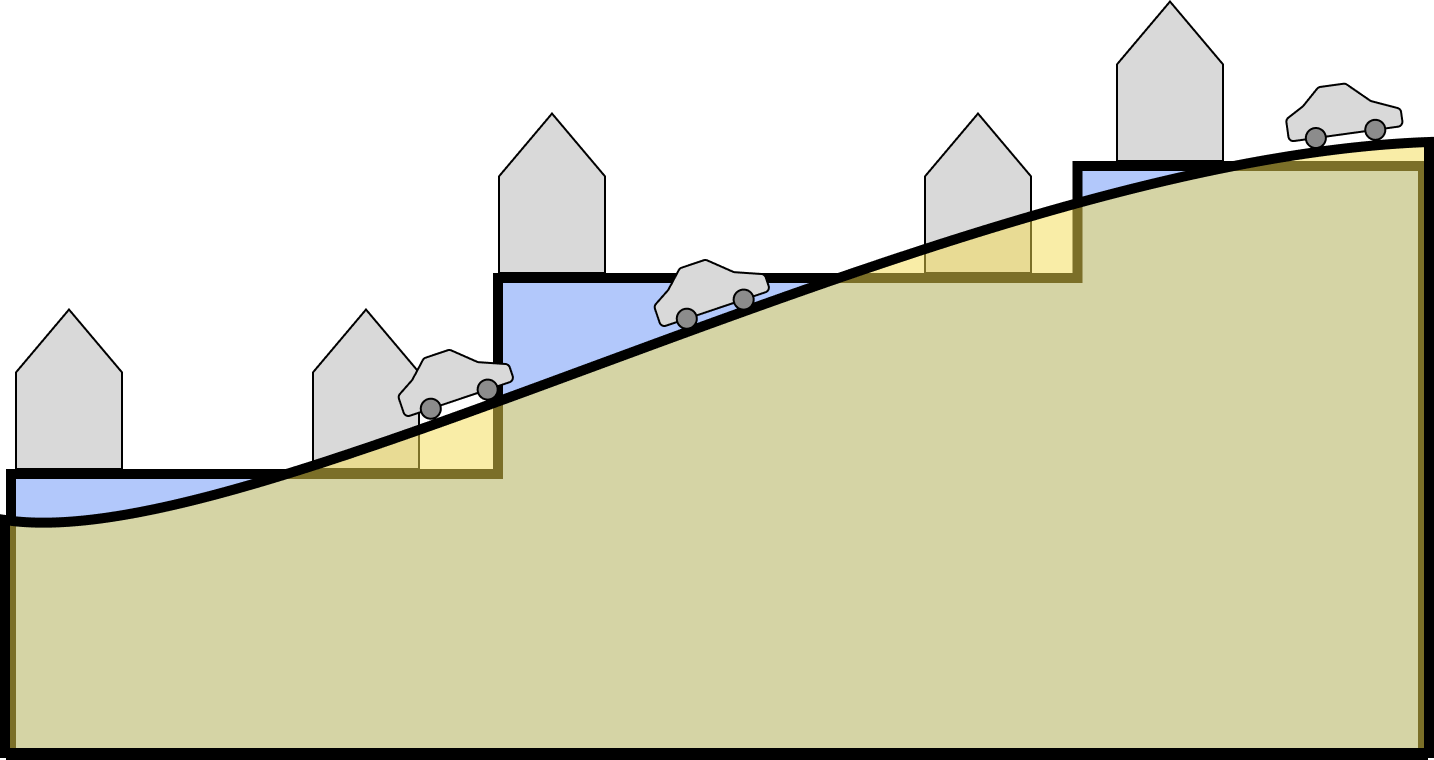

Anyhow, the street I lived on ran up the sloped ridge atop our side of the canyon. In order to have a flat place to build, there had been a huge cut-and-fill operation, shearing off the top of that ridge and forming a series of terraced construction pads on the one side where the homes would sit and a smooth-sloped area closer to the edge of the canyon for the road. If you could see a cross section of the whole thing, it would look like the graph of a midpoint Riemann sum: a staircase overlaid with a smooth curve.

My family home shared a pad with seven other condominiums: two fourplexes at a slightly obtuse angle to each other, making a lazy L. The concrete pads were probably first and foremost a convenience to the construction crews that built the condos, and secondly a convenience to the people that lived there, making it possible for them to drive their cars right up in front of the homes. But to me the pad was primarily a place to play.

Some of my neighbors were old couples (which at the time probably just meant older than my parents) whose children were grown. But there were also some families with kids around my age, and we would play all sorts of games outside on the pad: hide and seek, cops and robbers, kick the can, capture the flag, dodgeball, wiffleball, basketball, and so on. Living as we did on the steep hillside, the pad was the only safe place for kids to ride a bicycle or a scooter or a skateboard.

All of this throat-clearing about the geography of the canyon and the complex shapes made by the street and the pads has been partly (I admit) the kind of regrettable self-indulgence memoirists are always foisting on readers, but mostly (I hope) it’s necessary background to help you understand the next sentence. While I was growing up, there lived across the pad from me a historian named David Baird, and the bulk of our interaction during the almost twenty years we were neighbors was this: I made a horrible racket, pounding basketballs on the pavement and shouting with my friends and probably crying, right outside his home and he kindly put up with it.

It’s hard to remember now what I must have thought about Dr. Baird, to the extent I thought much of him at all, growing up. I think I had a sense relatively early on that I had unusually interesting neighbors. None of them had normal jobs like plumbers or nurses or insurance salesmen or dentists because I grew up in faculty housing on the campus of a university. So my neighbors had jobs with exotic names that—to me, at least—felt like filling in the OCCUPATION field on a form with “alchemist” or “knight errant.” My neighbors were all historians, philosophers, and mathematicians.

I don’t think I knew, growing up across the pad from Dr. Baird, that he was engaged in writing so many volumes about the history of Oklahoma, tracing the stories of the Choctaw and the Chickasaw, while I was outside playing H-O-R-S-E and trying not to let rebounds hit his Toyota. I don’t think I knew that he was busy studying changes to the college’s general education curriculum while I was busy traipsing through the bushes on the hillside right outside his door. I don’t think I had much of a concept of who he was apart from a neighbor we also saw at church on Sunday.

(I’m not trying to suggest I feel any kind of guilt about this, by the way. Kids will be kids, after all, and it’s not like I was a terror around the neighborhood who made it impossible to grade seminar papers on the couch after a long day at the office. It’s more just the sense that comes with aging out of the more self-centered part of childhood, where you realize that other people are leading their own richly detailed and intensely real-feeling lives and you should probably try to live in such a way as to be sensitive to them.)

What I’m trying to say is that I didn’t realize at the time that, while I was playing with my friends, Dr. Baird was devotedly building and maintaining and leading the institutions that would play such a big part in my young life and in the lives of my friends. He was a longtime elder at the church where I was taught the Bible and was formed as a young Christian. He was the chair of the humanities division where I would later study as an English major, no doubt having a hand (i.e., Baird did) in hiring and equipping the professors who would introduce me to Malory, Milton, and Melville. He was then the dean of the college where I would later meet my wife.

During the period of Baird’s leadership at the college, I was a child, almost totally unaware of what he was doing except when we had to pause our games on the pad to make way for him to park his car. There are many others much better qualified than I to speak of his qualities as a leader and as an academic. But that’s not to say I didn’t benefit from his leadership.

Institutions like churches and colleges resemble old cars: keeping them in good working order requires effort and careful attention. And as with an old car, if you inherit a college that’s running smoothly, you can be relatively sure that it’s working well because someone before you cared enough about it to keep it that way. When I left the pad and moved down the hill into the dorms to take my degree, I inherited a college that was the product of decades of work by Dr. Baird and people like him.

The story might have ended there—just a sweet memory about a kid who grows up and finds out what his neighbor was doing all those years. But when I think about Dr. Baird’s contributions today, I mostly am not thinking of his work on Oklahoma history, or his leadership in the humanities division or the college or the church, as influential as they were. When I think about Dr. Baird today, I think about a different project he undertook during my years in the college: a history of Pepperdine University.

Baird originally envisioned the project as a 400-page history of the university to be published for its seventy-fifth anniversary. But his plan to complete it in two years was foiled when his first draft stretched to 1,400 pages. The resulting book, Quest for Distinction: Pepperdine University in the 20th Century, came in at about 700 pages after seven years of research, writing, and revision.

In the preface, Baird humbly refuses to identify his book as the definitive history of the university, but it is without a doubt the best-researched and most comprehensive work available today, weaving together the various strands of the university’s past into a cohesive narrative. As a student of the institution’s history, I owe Dr. Baird a great debt for his book, especially for the way he charts the relationship between the university and the church. As good as the book is, though, I think the footnotes are at least as valuable as the text they accompany. It’s these footnotes that open the archives for future research.1

The Quest book was published in 2016, the year after I graduated and moved away from California. I was vaguely aware of it when it first came out—I think I read a few chapters in my parents’ copy. But over the past few years, as my interest in the university’s history has grown, Dr. Baird’s book has become an indispensable resource. I took my parents’ copy for myself, forcing them to get another. Now it’s all marked up with my notes and rarely leaves my desk.

When I’m not speaking carefully, I sometimes collapse Quest for Distinction and its author into a single entity, as when I think, “I’d better check Baird,” before consulting the book for answers about Pepperdine’s past. And in that sense, Baird is still with me, here at my desk.

It’s a strange fact of the discipline of history that historical narratives can affect the thing being studied. A geologist could speak to the sandstone walls of Winter Canyon for eons, telling them all about their origin in the Jurassic period, or about the chemical composition of quartz and feldspar, and all that talk wouldn’t change a single thing about the canyon. But Baird telling the university about its history can have tangible effects on the university itself. In that way, Dr. Baird’s influence will continue even now that he’s gone.

Opera illorum sequuntur illos.

I’m indebted to Dr. Baird even for this insight, which he shared in a panel discussion in 2011: “The most significant contribution I’m making is not so much the narrative as the footnotes.”

I remember at NSO in 1996 I went to a meeting for history majors, and Dr. Baird was running the meeting for the incoming freshman who were majoring in history (and maybe some other humanities). He wanted to go around the room and see where everyone was from. I introduced myself as being from a small town in Southwest Oklahoma—not far from the Texas panhandle. Dr. Baird proceeded to educate the entire group about my small town, its location and geography, and that it was well-known for being great area for cotton farming. I doubt anyone else in the room cared to learn that, but I was surprised and impressed at the time. I remember it now 28 years later.

Oh Sam, I so much enjoyed this one. I am so sorry to hear of the passing of Dr. Baird. Your recollections of growing up on the Baxter pad brought back so many good memories of when your grandmother and I visited you and your family there. And the activities that took place and the people who lived on and around the pad were always of special interest during those visits. Thanks for sharing!!