Pepperdine's other nursing program

This week Pepperdine announced that the Board of Regents has approved plans for a College of Health Science, with degrees in nursing and speech pathology beginning in 2025 and other programs to come. Congratulations are due to president Gash, dean Feltner, and the whole team for bringing Pepperdine one step closer to pursuing truth relentlessly in every discipline.

To celebrate the historic announcement, I thought we would focus on the story of Pepperdine’s other nursing program—not the new one launching in 2025, but a forgotten one that opened half a century earlier, in Vista, California.

In 1975, Pepperdine was all stirred up. Ronald Reagan visited the new Malibu campus to speak at the dedication of Seaver College. President Gerald Ford visited to dedicate the Firestone Fieldhouse and the Brock House. Buildings were still going up around Malibu, and women’s athletics programs were just getting going as the implications of Title IX began to become clear. Twice that year, the university was rocked with scandals: first during the Trent Devenney affair and again following chancellor Young’s accident. And president Banowsky was busy behind the scenes remaking the Board of Trustees into a new Board of Regents.

Largely ignored among all the excitement that year was the launch of a new off-campus program in San Diego County, offering night classes for working nurses in Vista and San Diego. Pepperdine was adopting a “university without walls” model and had thus gained quite a bit of experience offering non-traditional degrees off-site, mostly through its schools of business and education.1 The nursing program, however, was housed in the School of Professional Studies, which had been formed in 1972 when most of the liberal arts programming moved from Los Angeles to the new Malibu campus, leaving behind an assortment of mostly professional degree programs that had once belonged to George Pepperdine College.2

From the beginning, administrators wanted the nursing program to gain accreditation from the National League for Nursing (NLN). The program recruited a first class of students, telling them that the accreditation process had been initiated, but earning accreditation proved more difficult than anticipated. In 1976, VP for academic affairs John Nicks decided the program was not justified financially, and the university announced it would be shut down.

In response to the news, a group of twelve nursing students visited the Malibu campus to ask that the program continue through their graduation, explaining that the closure of the program would effectively prevent them from receiving training in Vista, where there were no alternatives. President William Banowsky must have been moved by their arguments because he agreed to reinstate the program and to continue the quest for accreditation.3

The first class graduated in April 1978, just ahead of a site visit from an NLN accrediting team led by Ellamae Branstetter.4 I haven’t been able to find the team’s report in the university archives (if it survives at all), but descriptions of it are mixed: Pepperdine regarded it as a favorable report while other observers thought otherwise.5 Either way, the report was not enough to prevent the nutricial bigwigs at NLN headquarters in New York from denying accreditation to Pepperdine’s program in January 1979.

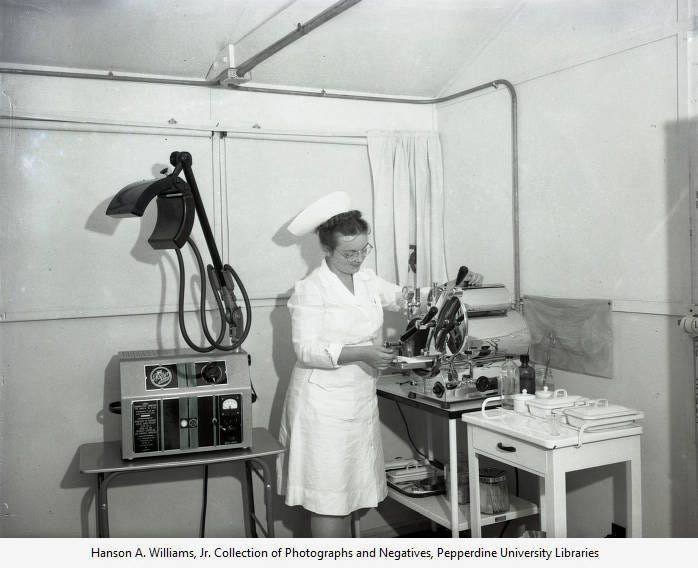

Pepperdine administrators were surprised by the denial of accreditation, attributing it to the NLN’s failure to appreciate a new form of nursing education, one that brought courses into the community where the students lived and worked. After all, Pepperdine had reinstated the program in 1976 specifically to make such training available to working nurses who didn’t have alternatives nearby. NLN countered that the program was too far from Pepperdine’s main campus and lacked the laboratory facilities required for such coursework.6 Unable to secure accreditation without a significant expansion of its Vista facilities, Pepperdine announced in March 1979 that the program would be phased out, and the last students graduated in 1980.7

But this wasn’t the end of the story. In February 1979, thirteen nurses sued Pepperdine seeking $220,000 for breach of contract, arguing that the university had lured them to enroll with the unfulfilled promise of accreditation. Pepperdine responded that the plaintiffs had known from the start that accreditation could not be assured and that its hands were tied by the NLN, who required that a program graduate a class before receiving accreditation.8 When the case went to trial in June 1981, the twelve-member jury found Pepperdine not liable.9

So much has changed since then that the story of Pepperdine’s nursing program in the 1970s may not offer many lessons to us today beyond the failure of the “university without walls” model. Pepperdine historian David Baird, reviewing a number of unsuccessful off-site programs of that period, summarizes them thus: “Experimental and innovative programing was all about receipts and cash flow and had little to do with the noble vision of a university without walls or a cosmic call to Christian distinctiveness.”10 Pepperdine is at its best when it upholds its vision of education, one that marries the educational process with the divine process and that treats each student as a person of infinite dignity, not just as a potential source of revenue.

See David Baird, “A University Without Walls,” Quest for Distinction: Pepperdine University in the 20th Century, Pepp. Univ. Press (2016): 199-207.

The college in LA went by a number of different names between 1972 and its closing in 1982, including College of Arts and Sciences, School of General Studies, and School of Professional Studies. I will use the last name for simplicity’s sake.

Lynette Kelly, “Pepperdine wins in lawsuit,” The Graphic, 16 Jul. 1981: 3, 8. Cf. John Berhman, “Pepperdine Blamed at Trial in Vista,” (San Diego) Union: 4 Jun. 1981. See also David Baird, Pepperdine University in the 20th Century: A History, vol. 1 (unpublished): 393.

Kelly (supra note 3) records the name of the head NLN visitor as Dr. Ellie Bransteader, but I suspect this is a typo for Branstetter, who was a prominent professor of nursing at Arizona State.

E.g., compare Ronald Helm’s summary of the report in Kelly supra note 3, with Wesley Peltzer’s summary of it in Berhman supra note 3.

Kelly supra note 3.

Ibid.

Bill Daly, “Nursing school sued over accreditation,” (Vista, CA) Press, in Box 4, Nursing case 1981 file, Pepperdine University Office of Public Affairs Records, Pepp. Univ. Special Collections and University Archives.

John Berhman, “Nurses Lose Lawsuit Against Pepperdine,” (San Diego) Union, 27 Jun. 1981, ibid.

Baird supra note 1 at 207.