President Gash announced that Pepperdine’s theme for this academic year is freedom. In recognition of that theme, I thought I would look into the history of the Freedom Wall and share my thoughts on the health of public debate at Pepperdine over the last four decades.

As far as I know, there hasn’t been much national news coverage of Pepperdine traditions like The Rock or Dolores, but there certainly have been such stories published about the Freedom Wall. The Freedom Wall is a free-speech bulletin board near the entrance of the Tyler Campus Center in Malibu. Its long history has been punctuated with controversy right from the start.

Where did the Freedom Wall come from?

The Freedom Wall began in the fall of 1986 as a project spearheaded by the Young Democrats, a student club working with the Campus Life office to designate a wall in Adamson Plaza for free-speech posting.1 It didn’t take long for the wall to attract controversy.

In January 1987, the Black Student Council (BSC) and the Sigma Epsilon fraternity accused each other in a series of postings, some of which were anonymously taken down (despite a rule that all posts should be left up for a week). The controversy started when the Sig Eps did a lip-sync routine at homecoming, re-creating Run-DMC’s “Walk This Way” music video, with their faces painted black.2 Then the posting began. The president of the BSC told The Graphic, “We are not saying they were racist or bigots; they were ignorant.” The president of the Sig Eps answered, “For us, black, Mexican or Oriental we don’t see color—they are all brothers.”3 This first tiff on the Freedom Wall captures the tenor of many controversies to follow: accusations, misunderstandings, and posters torn down.

There was a whole ecosystem of anonymous (or pseudonymous) posters on the Freedom Wall in 1987. The Graphic managed to interview one poster who went by the name “Cliffy,” and who remained anonymous for his interview. Cliffy identified as a far-right member of the College Republicans who enjoyed corresponding via postings with other pseudonymous posters including Cold Beans, Turbo, and Hugh Man. He appreciated that the wall allowed him to express controversial opinions on such topics as the Iran–Contra affair and sanctions against South Africa.4

The Freedom Wall thus played at least one of the roles of today’s social media: allowing open exchange of ideas on controversial topics between interlocutors who had the option of remaining anonymous. I’ve written before about the effects of (especially anonymous) social media at Pepperdine, and I suspect many of the same dynamics were at play on the Freedom Wall in the late ’80s.

Like so many student projects, the Freedom Wall required a renewed commitment every year as the student population turned over. In 1988, the wall was “reinstated,” as if it had ceased to be in the interim.5 And in 1991, it was “revived” again.6

The wall was evidently the site of some hot disputes in these years, especially over matters of race and sexuality. In 1992, a vandal relabeled it the Hatred Wall due to a perceived degradation in the quality of debate.7 But these heated exchanges were later regarded as a golden age of the Freedom Wall. In 1996, The Graphic published an ubi sunt lament, nostalgic for the days when students had had to elbow their way to the front of the crowds to see the latest provocative postings.8 This dilemma—denouncing bad posts when the wall was in use and decrying the lack of posts when it was neglected—would characterize much coverage of the wall over the ensuing decades.

By 1998, the wall was a dim memory for most students, slipping through the cracks during leadership transitions among the Young Democrats, who didn’t realize the project was their responsibility. The cork board was taken down so the wall could be repainted, and it wasn’t put back up.9

In 2000, the Freedom Wall was resurrected by the Amnesty International club under faculty sponsor Dr. Robert Williams. This time, it was set up across Adamson Plaza, closer to the student lounge now called the Light House.10

But this version of the wall didn’t last long. In the summer of 2001, it was taken down and a palm tree was planted on the spot as part of a makeover of the central campus plazas. The change occasioned more nostalgia: the wall had been a “magical square space,” and by removing it Pepperdine was showing “a lack of faith in the student body.”11

Before long, plans were made for a more permanent installation, this time to be overseen not by a transient student club but by the Student Government Association (SGA) itself. SGA president Ben Elliott met with university administrators to secure a wall of the Tyler Campus Center near the bookstore. The cork board was installed in the spring term of 2003.12

As far as I know, this iteration was the longest-lived of all the Freedom Walls, surviving to the present day, with a revamp in 2022.13

What gets posted on the Freedom Wall?

Most posts on the Freedom Wall are what you’d call ephemera—records of them don’t survive in the archives. But some especially controversial displays have inspired reporting in The Graphic, allowing us an insight into what has stirred up Pepperdiners over the years. Many of these posts were about issues of campus policy and university affairs, like policies around student use of alcohol,14 the hiring process for resident advisors,15 the decision not to rehire a popular professor,16 and the presidential search process.17

On the whole, I think it’s safe to say that posting on the wall has tended toward left-leaning activism, with major posts protesting heterosexual oppression,18 restrictive immigration policies,19 racial insensitivity,20 abuse of accessible parking spaces,21 and—yes—Chick-Fil-A.22

But there have also been notable posts from the right. The first controversy on the new wall in 2004 was an anonymous poster advertising a hypothetical “White Student Union,” asking in the fine print how the prospect of such a club made readers feel. Students and faculty were provoked into a “frenzy.”23

In 2017, visitors from Turning Point USA papered the Freedom Wall with posters saying things like “taxation is theft” and “Socialism SUCKS.”24 The posters were soon vandalized, then taken down. The Graphic opined, “Writing over and defacing opposing views is an unacceptable use of The Freedom Wall, no matter who posted what.”25 The whole ordeal inspired chaplain Sara Barton to post “A Poem for the Freedom Wall” in response.26

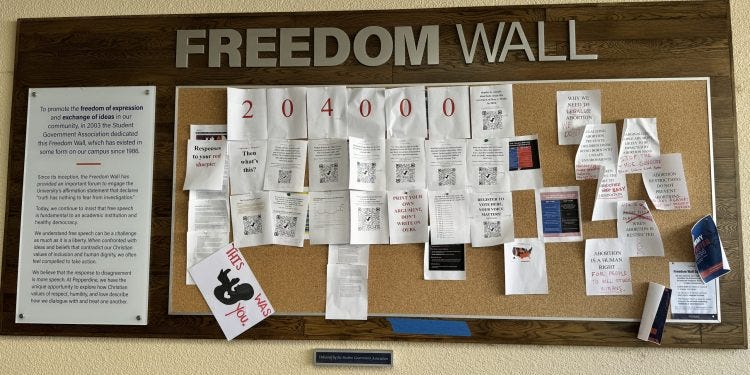

But the Freedom Wall event that inspired the most news coverage started with a memorial display organized by the College Republicans in 2021 for American victims of abortion. The display featured 620 paper crosses, one for every 100,000 abortions performed in the U.S. since Roe v. Wade. Soon after it went up, the display was vandalized by students who inverted the crosses, tore them down, or covered them with posters featuring pro-abortion slogans.27

The abortion conflict drew the attention of national outlets, including Fox News. In response to the coverage, Pepperdine issued a statement, gesturing toward support for free speech and the respectful expression of competing viewpoints.28

One of the constant refrains in coverage of the wall has been complaints about the low quality of posts there, often tinted with nostalgia for an imagined golden age. In 1996, Laura Hicks could look at the “eerily-empty Freedom Wall and remember when, at one time, it used to mean something. Now, fliers and promotional posters are stapled under these hallowed words.”29

In 2005, a Graphic editorial lamented:

“Instead of thought-provoking, community-building and challenging words being posted on the Freedom Wall, what stands out the most are the crass and vulgar words sprawled in plain view.”30

Again, in 2012:

“I remember when the Freedom Wall was a genuine resource for the discussion of human rights, theological doctrines, environmental issues, and questions of liberty. Now it’s the eyesore that is utterly ignored by everyone except for a certain few looking to push the next student coffeehouse.”31

New directions

In reviewing almost four decades of the Freedom Wall’s history, I’m not sure there ever was a golden age. Cliffy’s culture of pseudonymous posters in the late ’80s was the closest thing to the sort of free and sustained exchange of ideas the wall was designed to promote. I find little archival evidence of that kind of success after that era.

Over the last couple decades, even the serious and well-intentioned posts often strike me (in my darker moods) as moralizing takes on culture-war issues, poorly calculated attempts at point-scoring, jejune provocations ill-equipped to persuade, and betrayals of a sometimes shocking illiteracy.

Since the rise of social media, some have speculated that the Freedom Wall may be obsolete.32 Of course, social media has all the same problems I’ve just listed as well, but it also solves some perennial problems, like posts being torn down by anonymous dissenters.

But whether it take place on the Freedom Wall or the Facebook Wall, I think Pepperdine would be enriched—and its students strengthened—by more regular exposure to informed and reasoned arguments on important topics from a variety of disagreeing voices. Because developed arguments are better than slogans, blogs are better suited to this than posters; perhaps, though, a highly developed culture of pamphleteering would do just as well as a blogosphere. All it would take is commitment from interested parties.

For all its shortcomings, the Freedom Wall is not worthless. In fact, it has been cited as a model, even among Pepperdine’s rivals.33 It is a great compliment to Pepperdine that this history has been undarkened by the stalking specter of university censorship. In that way, the Freedom Wall has served and still serves as a beacon of free expression on a campus that has long prided itself on its commitment to freedom.

See Ernie Mantes, “Young Democrats,” Impressions, 1987: 88. Cf. Cindy Pazuk and Jennifer Burr, “Lip-sync performance results in controversy,” The Graphic, 29 Jan. 1987: A1, A8. In 1987, the wall is said to be in Joslyn Plaza, but I suspect it was actually in Adamson Plaza (closer to The Rock than the fountain). In 1988, it is said to be in the northeast corner of Adamson Plaza, which I take to mean the northern corner, nearest the Starbucks today. See Keith Sloane, “Young Democrats,” Impressions, 1988: 88.

In a weird coincidence, the music video that inspired the controversial lip-sync routine features a conflict between a white group and a black group, separated by a wall.

See Pazuk and Burr, supra note 1.

Joan Mackie, “Cliffy tells all; on and off the wall,” The Graphic, 3 Dec. 1987: A3.

Sherri Senffner, “Political clubs organized,” The Graphic, 29 Sept. 1988: A7. Cf. Sloane, supra note 1.

Jim Radosta, “Freedom Wall revived in Adamson Plaza,” The Graphic, 14 Feb. 1991: 3.

See photo by Ron Stearns, The Graphic, 15 Oct. 1992: 1. Cf. Staff editorial, “Students violate the Freedom Wall guidelines,” The Graphic, 22 Oct. 1992: 10. See also, Leslie Goodbar, “Faculty and students explore roots of tensions on campus,” The Graphic, 16 Nov. 1992: 6.

Laura Hicks, “The death of the Freedom Wall,” The Graphic, 28 Mar. 1996: C5.

Alyson Pitarre, “Express yourself,” The Graphic, 12 Nov. 1998: B8.

Lisa Wahla, “Resurrecting Pepperdine’s Freedom Wall,” The Graphic, 3 Feb. 2000: A4.

Nicholas Mah, “Freedom lost, palm tree takes its place,” The Graphic, 27 Aug. 2001: A11.

DeNae Thomas, “Free speech: Coming to a wall near you,” The Graphic, 23 Jan. 2003: B4. Cf. Jamilee Lambert, “SGA: New E-board set to take over,” The Graphic, 4 Apr. 2002: A10.

See minutes of the University Management Committee, 16 June 2022: 1.

Nicola Wenz and Mary Cate Long, “100 Anonymous Comments. One Voice That Set Them Free,” The Graphic, 23 May 2018. See also Channa Steinmetz, “Unite Pepp Movement Continues Conversation on Good Samaritan Policy,” The Graphic, 4 Oct. 2018.

Ashley Mowreader, “HRL reacts to angry Freedom Wall display,” The Graphic, 21 Mar. 2019: A1.

Vernie Covarrubias, “Social Media Fuels Movement in Support of Non-Returning Professor,” The Graphic, 18 Mar. 2020.

Madison Nichols, “Pepperdine Protests or Calls To Action?,” The Graphic, 31 Jan. 2019.

Sara Rosner, “Students Against Homophobia club can’t find sponsor for Tolerance Day,” The Graphic, 25 Mar. 2004: A3.

Lauren Morton-Farmer, “Students clash over immigration,” The Graphic, 6 Apr. 2006.

Ashley Mowreader, “Pepperdine Justice Coalition Protests for Action and Acknowledgment from Administration,” The Graphic, 12 Nov. 2020.

Lindsey Sullivan, “Students With Disabilities Continue to Petition for Change on Campus,” The Graphic, 29 Jan. 2020. See also, Maria Belen Iturralde, “Student with Disability Speaks Out Against Discrimination,” The Graphic, 2 Oct. 2019.

Alex Neis and James Moore, “Freedom Wall Saga Casts Light on Relationship between Pepperdine and LGBTQ+ Students,” The Graphic, 13 Nov. 2019; cf. Kayiu Wong, “Administration Says No to Bringing More Food Options On Campus Amidst SGA’s Push for Chick-fil-A,” The Graphic, 22 Oct. 2019.

Ashley Obrey, “Rock controversy follows a debate on hypothetical White Student Union,” The Graphic, 19 Feb. 2004: A4, A9.

Rachal Marquez, “Posters Removed from Freedom Wall,” The Graphic, 14 Jan. 2017.

Staff editorial, “Let Freedom Ring,” The Graphic, 26 Jan. 2017: A7.

Cote Keller, “Pepperdine Chaplain Sara Barton Writes Poem for Freedom Wall Denouncing the Freedom Wall,” The Author’s Files, 14 May 2017.

Laurel Wood, “Dueling Freedom Wall Displays Stoke Controversy and National Headlines,” The Pepperdine Beacon, 2 Oct. 2021. See also Samantha Torre, “Anti-Abortion Freedom Wall Display Creates Discourse,” The Graphic, 7 Oct. 2021.

Emma Colton, “Pepperdine University students vandalize pro-life display, rip down crosses,” Fox News, 2 Oct. 2021.

Hicks, supra note 8.

Staff editorial, “Post constructive comments,” The Graphic, 24 Feb. 2005: A10.

Benjamin Kryder, “Give us, us, The Freedom Wall,” The Graphic, 23 Feb. 2012: B4.

Isaac Randel, “Respect the Freedom Wall,” The Graphic, 8 Feb. 2018: A7.

See the begrudging admiration of LMU in Cristobal Spielmann, “Let’s turn the corner on campus free speech,” The Los Angeles Loyolan, 12 Feb. 2020.